What does a school counsellor do and how do you become one? It turns out that it depends a lot on where in the world you are! Most people are surprised to hear that mental health qualifications are not transferrable from country to country (unless they have a special reciprocal relationship that is, but most don’t). Although that seems strange, it starts to make sense when you learn that the same words mean different things in different places. It turns out that what a school counsellor (or counselor with one ‘L’ depending on where you are) does and knows and is responsible for is different in different countries.

Imagine it’s like this:

- Country A: surgeons are called ‘docs’

- Country B: nurses are called ‘docs’

- Country C: chiropractors are called ‘docs’

- Country D: acupuncturists are called ‘docs’

Start to see a communication problem? What happens when all those ‘docs’ from different countries get together to talk about assessment or treatment of clients? Not only will they have trouble communicating but they might not even know that they are having trouble – people often assume that they are all talking about the same thing when they aren’t at all. Or, they may find themselves in all sorts of conflicts without knowing why!

So What?

So we get stuck and trapped in our own frame of reference and we miss out on dialogue, resources, tools, professional experience, alternatives, knowledge, training, techniques, reflections – you get the gist right?

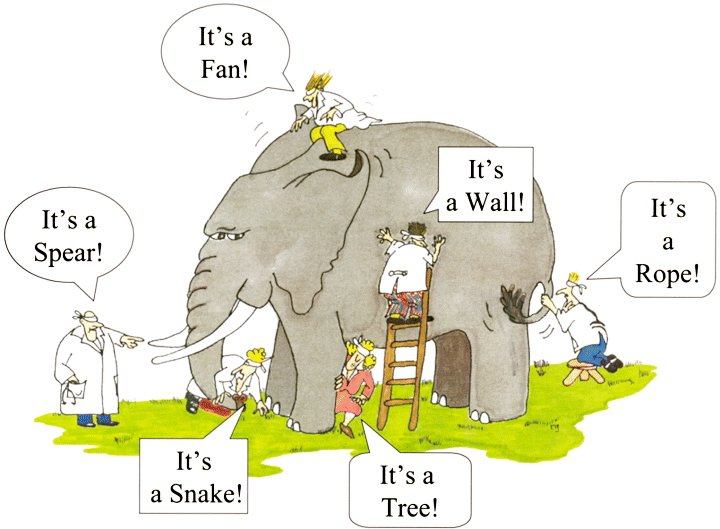

The downside of using the same word to mean entirely different things is that you don’t even know you’re missing out on anything though. Most school counsellors in one country don’t have much opportunity (or reason) to communicate with school counsellors in another. And as long as everyone around you is touching the same part of the elephant how would you ever know that there is more to an elephant than the bit in your hand?

I don’t want to drag out the ‘Blind Men and an Elephant‘ analogy indefinitely, but let’s say you and all your colleagues know a lot about elephant tails. That’s great for those kids who really benefit from some elephant tail. But what about the kids who really need an elephant trunk? Or the ones that would respond best to an elephant ear? You can’t offer what they need if you don’t know it exists and all you have is a handful (and brain-full) of tail!

I had to find out that the words ‘school counsellor’ mean different things in different places the hard way. It’s not that people try and keep this from you, it’s just that you don’t know what you don’t know – and hence can’t share it with anyone.

School Counselling in Australia

In 2015 I completed my (first) school counsellor training in Queensland, Australia. These days this means completing a Master’s Degree (1.5 years full-time!), but I snuck mine in just before research was a compulsory component so it was 1 year full-time. Well actually, mine was 6 months full-time because I had exemptions for half of it from a previous Master’s in Special Education (don’t even get me started on what special education means in different parts of the world!).

See in Australia, school counselling is a specialism that bridges the worlds of education and psychology. I’m sure there are exceptions, but as a general rule, being eligible to register as a school counsellor in Australia entails having a teaching license and a background in teaching, as well as training in psychology. The master’s I completed was a Master of Education and sat firmly within the world of education, despite extending tentacles into counselling and therapy. In fact, counselling skills and competencies comprised just 25% of the course content. The other 75% was focused on working ‘within the system’ and with all the stakes and stakeholders that entails.

One course was on consultation and collaboration so that graduates would be able to support student wellbeing by working with other staff as well as directly with students. Another was on assessment and testing, enabling graduates to conduct restricted access psychometric assessments and write reports for parents, staff, and other agencies. Another was on safeguarding and responding to trauma and abuse. The learning was geared towards the expectation that as a school counsellor you would be responsible not just for counselling individual students but working with families, schools, communities, school leaders, staff, and other services.

I think this has since changed but, at the time, there was no ‘counselling placement’ as part of training. Instead, after graduation I was required to complete a year of supervised (and paid), full-time school counselling duties before I was eligible to register as a fully fledged and independently functioning school counsellor in my own right. During that ‘apprentice’ year I would need to demonstrate that I was doing all the different things I had been trained for: running groups, supporting families, consulting with staff, conducting assessments, school-wide crisis management, as well as counselling children and young people. And at the end of all that, after my supervisor signed off on my work and hours, I became a full practicing member of APACS – Australian Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools. Yup, in Australia school counsellors have their own special registration body. Why wouldn’t they?

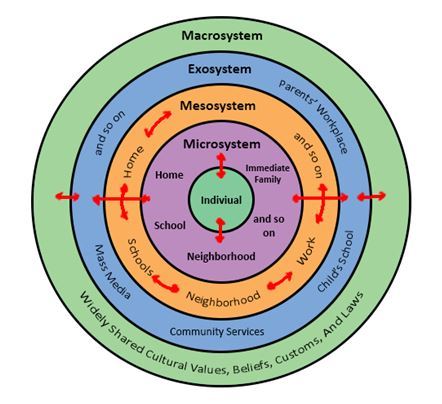

There were two big theories that underpinned my training as a school counsellor in Australia: Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory and Michael White’s Narrative Therapy. At the time though, I had no idea that these were big theories underpinning my Australian school counselling training. I just assumed that they were the big theories that underpin all school counselling training.

It didn’t occur to me that maybe, just maybe, White’s perspective was promoted because he happened to be Australian… I’m not that cynical! Instead I assumed that all school counsellor’s were trained to conceptualize individual distress as a response to a complex eco-system of people, organizations, and meaning-making in which they were embedded.

Duh, right? After all, what would the alternative be? Assuming that it was the child who was the problem? Trying to change the child’s inner distress without anything in the systems around the child changing?

School Counselling in England

After completing my Masters I moved to the UK to do my ‘apprenticeship’ year of school counselling in England. I wanted to get a breadth and depth of experience that I didn’t think was possible in the same way living and working in Vietnam or Thailand where there just aren’t as many English-speaking kids in distress. Mmhmm, I did my Masters in Counselling online while living in Asia – and this was before COVID-19 when studying online was a little bit like dating online in the 90s (the stigma: online is only for people who can’t do it ‘properly’ in ‘real life’).

Imagine my shock and horror when I discovered that school counselling doesn’t exist in England!

Well… that’s not exactly true. There are definitely schools in England and there are definitely counsellors in England and sometimes those counsellors go and do their counselling in schools and so they are technically ‘school counsellors’ (and advertised for as such) but it’s not a ‘profession’ in the same way. There is no Masters or other specific training required to become a school counsellor in England. There is no registration body specifically for school counsellors. In fact, it turned out that I wasn’t qualified to be a school counsellor in England at all – despite my specialist Masters level training for the role.

Now, you might be thinking (and you can bet I did) that I probably should have researched this before moving to England and finding myself with bills to pay. And I did try! I looked for school counselling jobs before moving and I saw them advertised – CHECK! You needed to have a counselling qualification to apply and I had all that – CHECK! And this is exactly what I mean by the difficulties that arise when we use the same words to mean different things. It just didn’t occur to me that the meaning of the words was different. There wasn’t even anyone to ask and clarify things because they didn’t know we were using the words differently either… it sucked. When I wrote that I had to find out the hard way I mean it was H A R D. I had two Masters of Education and I couldn’t even get an underpaid teaching assistant job working with troubled youth.

In England, to work as a school counsellor you generally need to be registered with one of the big accreditation bodies for counsellors and psychotherapists. I say ‘generally’ because in England the words counsellor and psychotherapist are not regulated, which technically means that anyone can say that they are a counsellor or psychotherapist (training be damned!). The biggest and most widely recognised accreditation body is the BACP, or British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy. The most common training route in order to register is a 2 year part-time counselling diploma and then you can start applying for school counselling jobs.

I was horrified. You don’t need to have any background or experience working in schools – even though they are really complex and unique environments. You don’t have to have specialist training in working with children and young people. You don’t need a university degree – let alone a Masters, in fact, most diploma courses are just one day a week! You don’t need to have any training in administering or interpreting psychometric assessments, in SEN, in consulting and collaborating with stake-holders, in developing SEL group curriculums, in writing reports, or multiagency working, or leading parenting skill groups. No training in any of the things that an Australian school counsellor is trained to do – and yet I wasn’t eligible for the job?!

I tried to apply to the BACP. I told them that I had done my Masters online and that it didn’t involve a counselling placement – 100 hours is the minimum in England. Nor had I been in therapy of my own. They were horrified. If I wanted to register with them I would have to retrain the British way. So I sucked it up and started a Diploma in Child Counselling – it was the closest thing to school counselling I could find. I would have to submit essays, complete a 100 hour (unpaid) placement, and be in personal therapy the whole time! I spent the whole first year feeling pretty confused about what I was learning which seemed completely different, and sometimes even conflicting, with what I had previously learned.

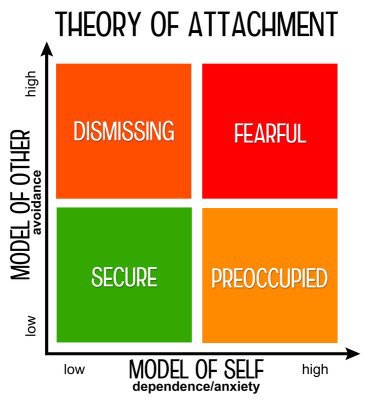

There were two big theories that underpinned my training as a child counsellor in England: Attachment Theory and British Object Relations. Again, at the time, I didn’t realise that these were the big theories underpinning my training. I was just really confused why no one ever seemed to mention eco-systems of the child, or critiqued the social constructions of ‘childhood’ and ‘disorder’.

It wasn’t until my second year that I even figured out that there were big and different theories underpinning my trainings and confusing me. And it was no coincidence that those big theories were big on Australian theorists in Australia and big on British theorists in Britain. In my Australian training I never heard the name ‘Winnicot’ or ‘Klein’, anymore than my British peers had ever heard of ‘White’ (or social constructionism for that matter!).

Implicit VS Explicit Knowledge and Learning

The sneaky thing about theories that ‘underpin’ is that they tend to remain implicit – they are there but we can’t see them, it’s like they are so all-around-us that we don’t notice them. They are not like specific counselling modalities or theories we learn about explicitly and can add to our toolkit, but more like the metal that the toolkit itself is built from. It’s not that Australian school counsellor’s aren’t aware of attachment theory or British school counsellors have never heard of narrative therapy – that would be much easier to recognise and remedy! What I’m talking about is the assumptions that are embedded in counselling training in different countries and which we remain unaware of – usually until they are confronted by an opposing view in which instance we usually end up in a conflict rather than becoming aware of our underlying and culturally-mediated assumptions!

I’ll give you an example: dual relationships. The first I heard of dual-relationships was in my British training when it was being explained that we couldn’t do our in-training counselling placement in a school where we had been a teacher. All the students nodded their head seriously, “yes, that would be bad”. Obviously. And if your training is built on foundational theories which involve transference and countertransference and object relations then you don’t really have to have the reasoning explained because it is already embedded implicitly in your understanding of what counselling is. And if your training is built on completely different foundational theories then you may be as confused as I was. In my first training, it was expected that I would have not just dual relationships with children, but triple or quadruple relationships. I might coach their parents, and consult with their teachers, and run workshops with their class, and write reports on assessments we did together, and provide individual counselling.

Which is better? Who was right?

I’ve been in the UK for 6 years now and had the opportunity to do a lot more training and a lot more thinking and reflecting. I did a year of systemic family training and found that it was much more similar to my Australian training in school counselling – the underlying theories and assumptions have a lot in common, like therapeutic cousins perhaps. I’ve found that my Australian training is so helpful for short-term work, group work, psychoeducation, and embedding mental health and wellbeing in school systems rather than being just what happens in one small room in the school. My British training has helped me so much in meeting the needs of children and young people dealing with complex trauma, in ‘holding space for distress’, and doing deep and long-term psychotherapeutic work. I’m grateful for the richness and diversity in my training, and especially thankful (painful as it was at the time) that having to retrain forced the implicit to become explicit, and hence something I can talk about. We can’t talk about what we aren’t aware of.

Share Your Experience

Are you a school counsellor? Would you be willing to share your experiences and what the words ‘school counsellor’ mean wherever in the world you are based? You can share in the comments or complete the Google Form questionnaire I have created just to find out more about school counselling around the world – or heck, do both! I think this is such a cool dialogue just waiting to happen…

Thank you for this, it is so helpful as I am looking into school counselling as a possible career change and I can see there are differences between countries in terms of the role and it’s training requirements. I am looking into countries that actually have school counsellors and what their training requirements are, would you have any further information on other countries?:)

I am only really familiar with English-speaking countries and International Schools. Is there a particular country you are interested in knowing more about?

In the USA the role really varies based on the State, City. Even each school is quite different and that can be the case for two schools across the street from eachother. For example, in the New York City public school system, counselors daily roles can vary greatly based on the needs/focus of that school. However, there are some generalities. The American School Counselor Association (ASCA) states that the role of the School Counselor (SC) is broken down into 3 main parts: Career/College, Social/Emotional, and Academic. Back in the 70s,80s, and 90s, there was a stigma that SC’s weren’t having a big enough impact on students, so ASCA made it a point to focus on the academic piece of their role. Hence changing the official name from guidance counselor to school counselor (SC). In the 2000s they also pushed a focus on data driven results. However, due to the recent increases in child mental health issues there seems to be more of an emphasis going back to the social/emotional components.

A good resource to check for available school counsellor positions in Europe is through TES which advertises vacancies in the UK and at international schools around the world. Another way forward is to research the international schools in the country you would like to work in and send some speculative applications. Hope that helps. You can check TES job search here: https://www.tes.com/jobs/browse/international